Wildlife conservation through the creation of national parks and reserves is a necessity to protect natural habitats from human activities. In 1872, Yellowstone was the first national park, many others followed since. Nowadays, several management models exist for conservation in Africa with heterogenic results.

Numerous threats pressure natural habitats: poachers, conflicts with farmers and economic activities. Unfortunately, national parks often lack funds to protect their territory, resulting in the loss of close to 70% of their fauna in some cases.

Other management models based on communities showed interesting results, such as in Namibia. Another model consisting in full management delegation of a national park is spreading across Africa.

In this article, we’ll give you an insight on each management model for conservation with a comment by Sergio Lopez, Wildlife Angel founder, to conclude.

Protected Areas

These lands are especially found in West and Central Africa but a few also exist in West and South Africa. They are often managed and funded by the country’s government.

3 Protected Areas Subcategories

Biosphere reserves and World Heritage Sites by UNESCO

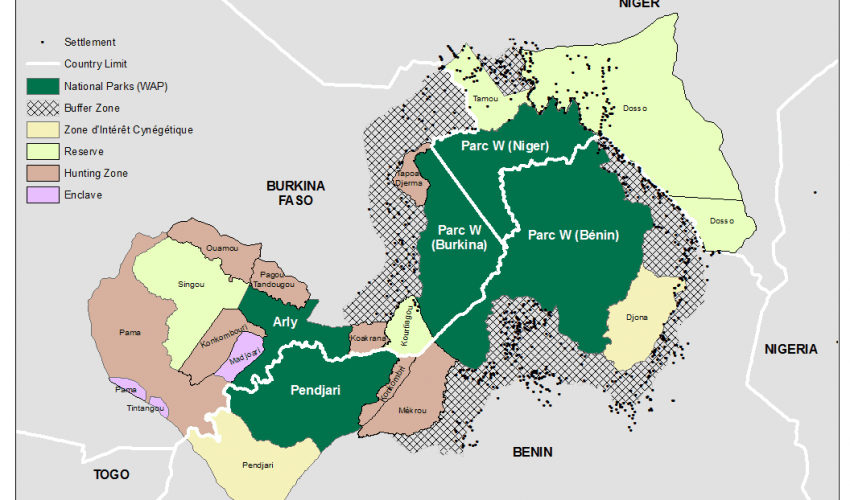

Protected Areas with an international aura like biosphere reserves and UNESCO reserves are registered as World Heritage Sites. For instance, the W National Park is part of the WAP Complex (WAP = W-Arly-Pendjari)) and has been listed since 1996 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The WAP Complex is a cross-border reserve in Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger.

IUCN Protected Areas: form I to VI

This part is from the IUCN website:

Ia) Strict Nature Reserve: Category Ia are strictly protected areas set aside to protect biodiversity and also possibly geological/geomorphical features, where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values. Such protected areas can serve as indispensable reference areas for scientific research and monitoring.

Ib) Wilderness Area: Category Ib protected areas are usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence without permanent or significant human habitation, which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.

II) National Park: Category II protected areas are large natural or near natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible, spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational, and visitor opportunities.

III) Natural Monument or Feature: Category III protected areas are set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, sea mount, submarine cavern, geological feature such as a cave or even a living feature such as an ancient grove. They are generally quite small protected areas and often have high visitor value.

IV) Habitat/Species Management Area: Category IV protected areas aim to protect particular species or habitats and management reflects this priority. Many Category IV protected areas will need regular, active interventions to address the requirements of particular species or to maintain habitats, but this is not a requirement of the category.

V) Protected Landscape/ Seascape: A protected area where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character with significant, ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value: and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values.

VI) Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources: Category VI protected areas conserve ecosystems and habitats together with associated cultural values and traditional natural resource management systems. They are generally large, with most of the area in a natural condition, where a proportion is under sustainable natural resource management and where low-level non-industrial use of natural resources compatible with nature conservation is seen as one of the main aims of the area.

Other Protected Areas

• Classified forests like the Sissili forest in Burkina Faso

• Hunting zone with a restricted access. Tourism is under control and hunting authorized with quotas and animal population monitoring.

Moreover, a protected area can appear in several categories. For instance, the Kruger Park in South Africa appears to be both a Biosphere Reserve and a National Park (IUCN II Category).

Some say we should increase our efforts on national parks and forests. But the lack of funding from governments is an issue. Other management models relying on the private sector exist and show encouraging results.

Private Reserves

These reserves are mostly found in southern Africa in countries influenced by the Anglo-Saxon culture: Namibia, South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

In most of the cases, these private territories are fenced. The landowner chooses the fences depending on the type of animals living in the reserve. He chooses how to manage his land and can decide to build infrastructures, lodges for tourists and make them pay an entry fee. However, some guidelines are to be respected regarding wildlife protection with hunting quotas. The same kind of rules apply for private reserve only proposing tours and safaris.

Example: In Namibia, a private owner may have several black rhinos on his land but – in theory – it is totally forbidden to allow hunters to kill one of them as the species is registered on the IUCN Red List as in critical danger.

Private reserves in southern Africa buy and sell animals on markets. This is a common practice authorized by the law but owners cannot do what they want. For instance, they need a specific state authorization to buy a species coming from other countries. Besides, the wildlife they introduce has to be adapted to the habitat.

The rules on animal protection and management are decided by the government. International regulation on endangered species trade is made by the CITES (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species).

Conservancies

Conservancies embody a 3rd management model for protected areas in Africa. Widespread in Namibia, the country accounts for more than 80 conservancies. Following the Namibian Independence, the government kept only a few national parks like Etosha and Namib-Naukluft and gave the management of other areas to the local communities. They are in charge of tourism, hunting and wildlife management. These conservancies can range from several thousands to millions of hectares.

In 2006, there were about 40 conservancies in Namibia. Nowadays, this number overpassed 80. They are based on the CBNRM model (Community Based Natural Resources Management). Each conservancy chooses their business model: eco-tourism, hunting and sometimes both.

Conservancies relying on hunting

Depending on the type of wildlife living on the territory, a conservancy can focus on trophy hunting to generate revenue. But the government decrees strict quotas and animal population follow-up.

Villagers deal with private companies (travel agencies, safari agencies, etc.) to install camps and attract tourists. The staff (cook, cleaning lady, and guide) is recruited among the local community.

Conservancies relying on eco-tourism

Some conservancies prefer to rely on eco-tourism rather than hunting. Here too, local villagers sign contracts with private companies in order to build infrastructures and lodges. It also implies attracting more tourists because observation generates less revenues than hunting. Indeed, hunters pay an extra fee depending on the trophy.

In order to stimulate the local economy, there is a preference for local products harvested by farmers. In Namibia, the Caprivi region is wet enough to allow villagers to grow crops and sell their products to lodges.

In both cases (hunting and observation), conservancies sign contracts with private businesses in charge of promotion, communication and marketing to attract tourists.

Some less attractive territories suffer from isolation, rough climate and lack of wildlife diversity to attract travelers. Kaokoland in Namibia is the Himba’s territory and they have very isolated conservancies struggling to generate revenues from tourism.

According to IUCN, the conservancy model based on local communities shows the best results regarding wildlife conservation in Namibia, Kenya or Tanzania.

A new model for wildlife park management?

Some National Parks have lost from 60% to 70% of their fauna, sometimes even more. In Tanzania, Congo, Benin or in Malawi, we need to rethink the way we manage wildlife parks. Threats are numerous: loss of habitats because of unsustainable farming and mining, poachers killing animals and installing traps, etc.

National parks are failing to protect their fauna and lack funding.

Based on this assessment, another management model is emerging consisting in the privatization of a national park. It means that park management is entirely transferred to a private entity. The government signs a 20 year contract allowing a NGO or a company to benefit from the park’s resources in exchange for an annual income.

At the moment, the only structure able of doing so is African Parks. They manage 15 parks and plan to have 20 parks under their management by 2020, which is a surface equivalent to 10 million hectares.

African Parks promotes their local impact on communities with recruitment among the locals. They also attract tourists, rehabilitate airfields, infrastructures, and build schools and free clinics. To improve attractiveness, they transfer animals. Recently, they transferred black rhinos from South Africa to the Zakouma National Park in Chad.

African Parks put a stress on the economics and on the business orientation of their projects. They organize tourism, activities in the reserve and protect animals with anti-poaching units. Rangers have the right to arrest people then hand them over to the police. Besides, they can shoot for self-defense.

Territories under African Parks management are often fenced, which is sometimes an issue with villagers or farmers accustomed to cross the park.

Sergio’s insight on conservation

“At Wildlife Angel, we think that the best suited management model for wildlife conservation is the one involving local communities. They should be given an active role in their natural capital preservation.

International NGOs should not entirely stand in for local communities to manage their parks. Partial privatization of a national park works better with countries with an Anglo-Saxons culture, but less in francophone countries in West Africa where locals can feel dispossessed.

On the other hand, the economic dimension of a project plays a major role in its success. Without economic returns for the locals, failure is bound to happen. It can be challenging to associate revenues and environment protection, but it’s necessary.

We expect to develop new management models for national parks in Burkina Faso and Niger in the coming years. But with the threat of terrorism impacting tourism, times are difficult. We are dedicated to protect the fauna in both countries and hope we will be able to develop eco-tourism soon.”